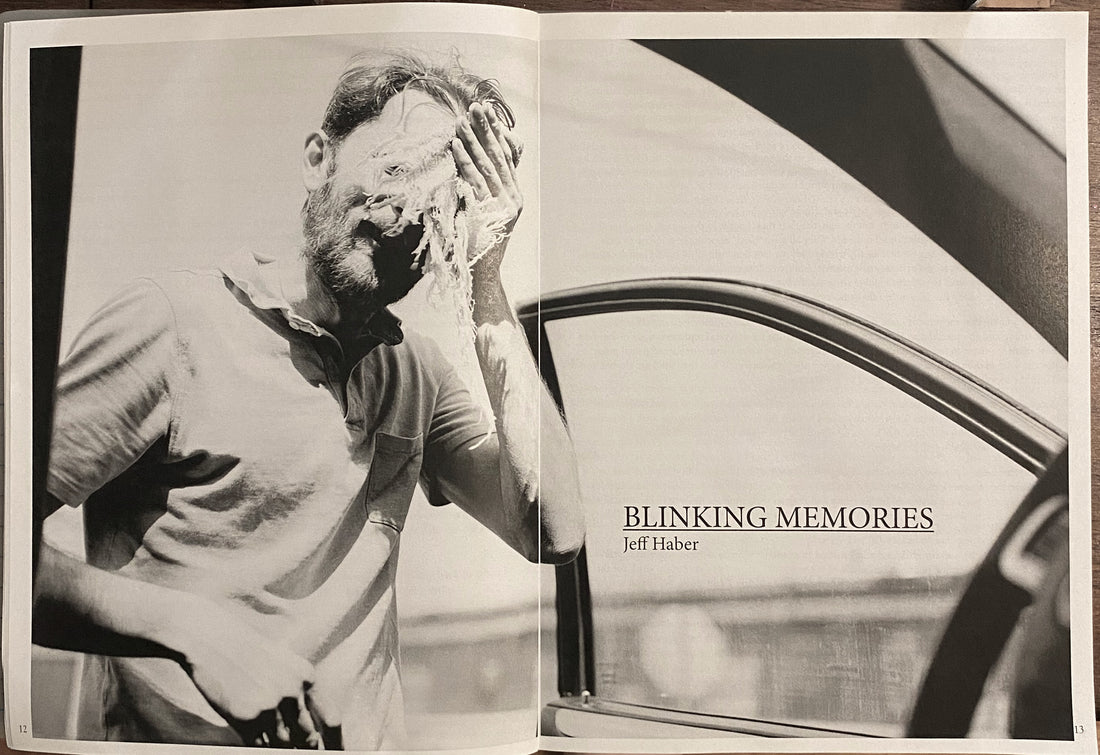

Blinking Memories (Published in Curlew Issue No. 9 - Winter 2022)

I.

I endlessly scrolled and clicked at work. The filing cabinets at my back silently mocked my ambition. To be something, somebody, whose voice commands listeners. At the front of the open-floor-plan office, behind the glass, the attorney and the expert commiserated on immigration. A whiny ambulance siren wafted up to the eighth floor from 31st Street, traveled with piercing frustration down the block, bounced from one wall of skyscraped business to the other, and then faded into the indifference of Broadway.

I took my phone out of my pocket. Tom sent me a link to the song “Flesh into Gear” by CKY, which we listened to when we were best friends at 13-years-old. “This came on Spotify and I immediately thought of you,” he wrote.

Skateboarding and causing mischief brought us and a bunch of other kids very close together for approximately three years. Once puberty hit, though, they left their boards in the garage, bought a few Big L CDs, and smoked blunts in schoolyards. They all went 'hard.' Shockingly, none of us ever considered there to be anything fundamentally wrong with the fact that Italian, Irish, and Jewish children appropriated the popular media's portrayal of Black culture, or adopted a cartoonish, minstrel-like affectation for their voices to sound tough or scary. As if they had a right to do so. As if any White person could ever justify this bizarre entitlement.

Instead of joining that movement - one that embarrasses me even now - I immersed myself into skateboarding and shunned the world of Long Island. Imitating stereotypical representations of hip-hop culture made no sense to me. Especially because underneath the white t-shirt-gowns and pencil point sideburns were middle class ideals waiting to take over after graduation. When they shed the clothes and slid into the viciously average boxes glorified by the community.

A decade later, I called it privilege and sought to educate myself so as to become a respectable White. Not a falsely apologetic one who seeks to extend and benefit from unfairness. Not one with a selective, convenient memory. Not one who uses lovers or friends or colleagues or acquaintances of color as an excuse for their own despicable character.

Tom is on the rise as a personal trainer after doing a four-year-bid for slashing a bouncer in Franklin Square. Working to achieve the highly sought after detached, single-family home lifestyle that his folks embodied before they were destroyed by his crime and their misadventures with heroin. He even missed his own dad’s funeral when he died from an OD. I assume he quietly cried in his bunk upstate. “That’s very sweet of you. Hope you’re well,” I replied to his text.

Some months went by, and my girlfriend and I moved from Greenpoint to Astoria. I tried to figure out how I could stop writing petitions on behalf of international artists and never again work for the Midwesterners who ran the firm. After looking at hundreds of portfolios in various fields and across a wide range of disciples, I began to feel an urge to put more effort into my own creative future.

I gave hundreds of thousands of words to these artists, and proved their "extraordinary ability" in order to procure a three-year O-1 visa or a Green Card over and over. But my hatred for the thankless nature of my daily writing tasks, laser focused on the insipid visual products of the upper class; the passive-aggressive and amateur management tactics of the expert, who was mentioned in Cuomo's 2009 immigration fraud investigation; the bald head and flabby belly of the spectacled senior editor, best childhood friend of attorney, and his disdain for me; the shit that I cleaned off the back of the toilet seat countless times, left there by the attorney; and the silence that grew between me and all my coworkers because I wanted to reach my full potential as a writer, not simply come in and then go home with a check…the hatred became too cumbersome and consumed my thoughts well after I shuffled out onto the street at 6 p.m.

On days when I walked across town to meet my girlfriend on the West Side, I transformed my dissatisfaction into madness and directed it at strangers with shoulder checks, cursing, punching taxi trunks, etc. I once stomped my foot through the rear spokes of a Citi Bike wheel because the operator decided to wait in the crosswalk for the light to change.

I also started to have trouble with the growing sense of complicity related to passing off clear bullshit as rarified gold to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service, bolstered by press coverage and testimonials from notable people such as Sting and Tina Fey, which I composed. I did not want to turn into a dirty scribe and shamelessly feed off the blood of the rich without even so much as an idealistic company mission statement to console me.

Then, at a friend's party in Bay Ridge, I met an Australian PhD student who wanted to interview me for her Rutgers dissertation on privileged immigration. After our discussion at the Starbucks on Steinway Street about forms and strategies related to high-end, mostly White migration, I realized that a year-and-a-half of my time at the firm was enough. I resigned the next day.

II.

Following an interview in the Financial District for a position as a writer at a new surveillance App, I headed up Water Street and looked at the first spots I skated in New York City 15 years earlier.

The air was damp and chilly, the sky whitish-gray like the froth on a rough ocean. I rolled and smoked a cigarette with shaky hands and slowly collected mist on my parka. My stomach was empty. At the Seaport, I took a photo of the building where me and many other skaters used to eat when it housed a Wendy’s. If it was not replaced by an expensive whatever-the-fuck, I would have gone in and inhaled a nostalgic cheeseburger, fries, nuggets with barbecue sauce, and a Coke with too much ice. I sent it to my friend Dan, who replied, “That makes me sad.”

The Banks, perhaps the most iconic and unique skateboarding destination in NYC, were still fenced off after a decade under the terms of a refurbishment project. The tall, cascading embankments of ancient red brick situated on a slight hill remained silent.

I stared at the fence and recalled how I put on a red Target t-shirt with a velvet Bruce Lee head printed on the front and went to the 2005 “Back to the Banks” contest with my buddies from Lynbrook to check out the pros. It was almost magical to see live skaters perform on the level showcased in the VHS tapes I had memorized. Anyone present was open to compete and could potentially win cash if their trick was impressive enough, but it was very intimidating. At one point I jumped into the mix, fought my way through a massive screaming crowd of testosterone to ride up a piece of plywood laying on the bottom six steps of a 10 stair, and attempted a double-kickflip over what's known as a euro-gap. I was getting close and had stuck one or two. My friends cheered me on from the side and I could barely hear them. My heart raced. Then a local pro from Flushing, Rodney Torres, snaked me and did the very trick I was trying before I could land it, so I bowed out.

While my identity as a skateboarder has been essential to my well being, the lack of purpose in the activity insofar as a career of any kind is concerned only grows as I get older. There is also an arbitrary and pointless aspect of the endeavor, because I do it for free, that lends itself to absurdity. Simultaneously, after 30 it carries a certain amount of guilt or shame because I feel like I’m playing a child’s game. I see my young self in the wrinkleless faces of the teenagers at the park and question why I continue to be dedicated. The act becomes encumbered by thoughts of responsibility, and to keep myself clear of them while skating is almost as hard as picking a trick and landing it. I try to block out everything, commit to my single mission like a dog, and engage in my own version of meditation.

And yet still, when I land something it brings relief, and overwhelmingly, skateboarding has been a constant source of momentary happiness, unrivaled adrenaline, and innocent fun. So I keep doing it, molding and shaping my creativity onto the concrete and asphalt and steel of the city, regardless of the social consequences or the isolation. I accept and interpret the sheer silliness as a fair exchange of stress for clarity.

I come from the generation of skateboarding that sought – over everything else – to fuck shit up. To assess the landscape and translate its mundane resources into a story of anarchy and individuality. To confront and assault the environment until the eyes of the status quo pop out and fall in the gutter. To dismiss the messages of conformity promoted by peers, parents, teachers, and cops. To conquer public and private property with a piece of wood fixed onto four wheels.

I suppose these unnecessary strains, primarily the pressure to define skateboarding and myself as rebellious, derived from my dad’s disapproval of the pursuit in my early adulthood. He equated it with being a dirty stay-out, a deadbeat, aimlessness, unemployment, and a difficult path that was sure to conclude at zero. When I would try and explain my choices he would respond with “That’s existential” or “Have you been smoking pot?” In fact, skateboarding prevented me from smoking, drinking, and dabbling with drugs until I was 20-years-old. I never went to a high school drinking party. Instead, I was out in the dark filming tricks with other kids who wanted a relatively healthy thrill. To his point, there was a period where I hung out with drug users and so-called losers, but I never partook and felt a kinship to them because they identified with the street, shuttled me around to spots, and provided me with a sense of camaraderie.

In the spring of freshman year, I dramatically abdicated my responsibility to uphold any further respect for my dad’s anxiety that I would imminently fail if I didn’t follow “the rules,” a concept that also was propagated by the community.

I wanted to leave my high school and attend a different one at night, or just assess my options for an alternative, as the curriculum wasn't challenging enough. I shared these desires with my mom, and she accompanied me when I met with my guidance counselor Mr. Caramore to have a discussion. He said, “Sure, you can drop out of school, attend night classes in Long Beach, and get a job. You’ll work for a few years, maybe at a drugstore, realize it sucks, and then want to go to college. It’s up to you, but surely it can be done.” My mom backed my decision either way.

To treat my dad fairly, and because I was living with him, I informed him of my ideas at dinner. He reacted with blind anger because he felt like I had gone behind his back in speaking with my mom and an authority figure without him, and basically declared that I would not be a dropout and do whatever I pleased. To match him, I too became enraged. Then I doubled-down, got up from the table where he and my sister sat eating some burnt divorced-dad-food he slapped together, and made for the door.

My sister protested the dysfunction but my dad insisted at a high volume, “Let him go,” to make his position known to me and anyone who may have listened through the walls or the open windows. He changed his mind, however, once I stepped outside of the front door into the hallway of the building and proceeded to leave. He followed me to the stairwell and tried to dissuade me from “fucking up your life” with a torrent of threats and warnings, then grabbed me by my hoodie. I clutched his undershirt in retaliation and shoved him down the stairs, but he held onto me. We traveled together, step by step, as he thumped each one in his white Gold-Toe socks from TJ Maxx, until we reached the landing before the next flight. He shouted, astonished, “You want to throw me down the stairs?” and then punched me in the side of the head. Emotionally hurt, I screamed, “You’re going to hit me in the face?” and cried as he let go. After the altercation, I walked out slowly through the sleepy streets to my mom’s apartment one mile away.

The following evening, I returned to my dad’s to collect whatever belongings I could carry with me, tucked my cat Biskit under my right arm, and left for good – I never lived with him again.

III.

In sixth grade, I saw a kid named Hubert roll on his board in the parking lot of South Middle School and float a kickflip. He not only rode a board but could speak through it. That seemed like the most subversive thing in the whole world. The power inherent in this physical form of expression captivated me beyond anything I had previously encountered. Out of a necessity to survive the malaise of my insignificant life on LI, I befriended him. Which meant, I approached him, mumbled something, and he said, "Go home, grab your board, and meet me at Jamaica Bank."

On a humid afternoon in May of 2001, Hubie, his older brother Roger, and their crew of Larry, Dave, Mike, and Alberto hucked tricks down the four stair in front of the bank. Their boards almost shot out onto the freshly paved tar of Merrick Road with each try. The sun was bright and the odor of sunscreen and boy-armpit lingered in the air. We went from there to the high school, the kindergarten center, 7-Eleven, behind an apartment complex off of Atlantic Avenue, and then to Marion Street School.

Before this, my skating was centralized, in that I'd grind a curb or jump off a kicker ramp in a driveway. But this crew taught me how to move from location to location and apply my skills as best I could on a given day, in the moment. How to assess the energy of a venue, in the same fragile and unpredictable way one does for a performance, and disrupt the stillness of the atmosphere with enthusiasm and rage. To attack the town I was trapped in within the context of my own unformed life-narrative and individualized movements. To subvert the indifferent scenery, representative of a sociopathic, cold, and racist incorporated village, and overcome its ignorant and dangerous limitations.

This frenetic and itinerant approach allowed me to build endurance, discover motivation, and hone my mental strength. I knew I had to follow this path, to absorb unfathomable bodily harm for a slight mistake, and to accept that pain and failure to gain success; to roll away clean and return to the blissful state of a toddler. It was a way for me to wring joy from an old rag that had been soaked in hatred for centuries, and uplift myself and those around me.

Surprisingly, and perhaps due to the difficulty of acquiring the skill or the consumer trends and effective marketing campaigns of the era, I earned respect and experienced the results of my labor both immediately and over time as my reputation in the community grew, inside and outside of skateboarding. The act was crucial to my daily life. I carved out a shred of freedom and used my board as a weapon and a shield to fight against what otherwise seemed a dead-end road lined with miserable people in Lynbrook, USA, who aspired to attain complacent and mediocre comfortability.

Like many common American suburbs, it's a place built upon an exclusionary ideology and cared for by an abhorrent and toxic citizenry. Those who have conjured an absentee racial identity, also known as White, and who utilize coded and explicit language to obsessively confide in and retain all those they deem members by visual analysis. People who believe in the masculine patriotism of foreign-manufactured consumer products, such as the flag and all the crap printed with the flag or its colors. Along with countless other corporatized images and manifestations that represent nationalism or the superiority of a loosely defined great White race, like tobacco, liquor, firearms, automobiles, motorcycles, boats, red meat, rock and country music, a passion for criminality that walks in step with a defense of any reprehensible police conduct, and an affinity for Martin Scorsese's catalogue of extremely violent films.

An environment very specifically designed, out of terror, to ensure a lack of questioning and total acceptance of the advantages of membership, without acknowledging the advantage. Whose ranks never ask themselves if or why they belong, for it is their birthright and the only way. As the big boy, God, intended. Just the way it is. As if natural, fair, and deserved. With no mention of the millions of non-White people who suffer, right now, to make the Lynbrooks of America possible. Those who can't become White, who live a few houses over, in the next town, and deep in the city.

No one ever said to me, for example, "We have an agreeable middle-class life because millions of people in the US and all over the world don't. We depend on the slave-wage labor of people of color to make our daily lives and superior position possible. If those expendable classes of humans weren't dying to facilitate the production of cheap goods and services, we couldn't live at this level. We need them to stay in their lower position, vulnerable and ripe for exploitation, because we rely on their destitution in order to extract all we can from them, and remain clueless and unconcerned."

Instead, I had to observe and formulate this understanding by myself. A knowledge that irreversibly obliterated any working, equitable, or sane relationship with that community.

And I credit skateboarding with initiating the pursuit of these truths, as it exposed my insular perspective and demanded an adaptation to diversity, and by extension, recognition of systemic unfairness. Which is to say, skateboarding eventually drew me into NYC and showed me the face of poverty and struggle that is so blatantly obvious here, especially in the outer boroughs. It made me see the reality that there are more who don't have than do have, and that race has a major impact on the type of life one is born into.

The arrangement is not accidental, based on merit, or ordained by a higher being, so far as I can tell. Rather, the situation appears to have been produced in such a way as to keep non-White people in an eternal, destructive cycle of poverty, struggle, and death, generally. Because high crime in concentrated areas enables uneducated, less-rich Whites to have jobs as modern day plantation overseers; and educated, wealthier Whites in the business sector and governmental positions to manipulate poor bodies and taxes in their favor, for maximum profit. Because cannibalism.

And as a failsafe, just in case there is an uprising, the Whites have drawn out a bureaucratic literature that is more complex and incoherent than the bible to guarantee them the agency to defend the right to live in this manner, at gunpoint or with a ballpoint pen, in service of their greed. Agreeing directly or indirectly, admittedly or in denial, that some human lives are worth more than others, and that one of the most important factors ought to be, as it has been, the color of your skin.

IV.

In 2004, a skateshop opened up in Rockville Center, just one town east of where I lived, called Harbor. For a while, I became a fixture in the shop and hung out with a group of kids who went to Chaminade, a Catholic school near Roosevelt Field Mall. The guy who worked there, Jimmy, was a 20-year-old wannabe cult leader with a used Honda Civic and pedophile vibes who took us skating at night and on the weekends. Through him I was given a shot to join Underworld Skateboards, the board company run by one of the shop’s owners, Mr. Kinirons, who took notice of me through the tape I made and edited on site in the back of the shop. I would film a clip, plug it into the TV, and record directly onto the tape. On two occasions I met with the Underworld team, which was comprised of men in their 20s and 30s, to show them what I could do, but nothing ever came of it because I was an aggressive kid and weaved in and out of them during the sessions, so was deemed "not a good fit."

Those kids in RVC were the first ones who I went with to skate the city, which everyone talked about but hardly ever did. The reason most often given was a lack of money but I knew that was not true. I can’t cite one kid I grew up with or around who really had a want for anything. They were always fed, clothed, housed, and relatively clean. And all the other accoutrement they had in their houses with lawns and backyards and driveways with usually at least two cars parked in them, really proved their access to let’s say, $15.00 in cash. Some lived in apartments or two-family houses by modest means, but certainly not in poverty. More than likely, fear kept them from heading in, a fear they readily accepted from their parents - the same fear that drove these provincial people from the urban landscape to a suburban haven for racist Whites back in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.

Andrew, Tim, Frank, and Mike from RVC, and John and I from Lynbrook took the Long Island Railroad to Penn Station, got on the E Train to World Trade, and skated up Water Street to the Banks. Afterward, we took the E out to Jackson Heights, transferred to the 7 Train, and rode that to Shea Stadium to skate in the fountain underneath the globe at Flushing Meadow Park.

It was November and cold. The streets had that worn, dusty look, created by the salt the Department of Sanitation uses to prevent slippage. I had on my Nassau Community College sweatshirt - navy blue with green lettering, which I got from my sister who went there, baggy Levis, and Koston éS low tops with a Rastafari color scheme. My hair was below my ears and shaggy. I was a skate rat.

As I messed around on materials trade union workers and day laborers killed themselves to construct in the downtown area and then out in Queens, I entered into an unexpected consciousness. One that felt correct and beautiful. As if I was supposed to be there. I experienced an unknown sense of meaning because I had made something completely my own, on my terms, in a relentless and indiscriminately brutal city. I didn’t need approval or a coach or a uniform. Just the small amount of money to get there, my board, and my determination. I was entirely present. My body and mind were clear.

Later on in that same year, I figured out how to circumvent the LIRR by riding the N4 bus from Lynbrook to the E at Jamaica Center, and coordinated the transfers to result in a total 25 mile round trip cost of $4.

One day, an older Black woman yelled at me in Jamaica Center. I was under the impression that I, a teenaged White kid, could play anyway and anywhere I wished just like in my hometown. So I went and skated on the embankments that line the walls of the station. In response, she screamed, "Take that bullshit back to where y'all live. Don't come over here and fuck up our shit. Go back to where y'all live and fuck up your shit." And another man jumped in to add, "That's right. They're fucking up my hustle." The attention of all the commuters and lingerers turned to me and my friends.

At the time I was scared, and for years, whenever I spoke about the event, I emphasized the fear I felt in that moment. But I don't see that as the point of the story anymore. I simply believe she wanted me to know my privilege and to show respect when I entered a space that did not belong to me and those who look like me.

V.

After Hubert retired from skating in high school, his brother Roger and I became close, and would venture to Manhattan, Queens, and far-reaching parts of LI on a weekly basis via bus and train. I met other people, too, like Will, Neil, Colin, and Mclane, and would ditch class to go skate. By the 11th Grade, I had whittled my schedule down so I only had to appear from 8 a.m. to 12 p.m., and continued to invest in skateboarding, even if I was alone. There were two younger kids that I aligned myself with so as to have a filmer on hand: Greg and Ray. Once I got my license I’d beg my mom to borrow her white Jeep Liberty and packed it full with my friends to hit Coney Island, Nassau Community College, the Roslyn Train Station, Midtown and the Unisphere at night, and everywhere else we knew or heard about. I would also drive around for hours looking for something different to skate.

In those days, I would ask anyone who skated or used to skate for their old boards because I burned through them quickly. They saw my talent and probably figured there wasn't much harm in letting me activate an unused piece of clutter. A toy they no longer wanted.

I steadily maintained a progression as a skater up to the age of 18, which is when I first traveled to North Brooklyn. I adored the patchwork buildings, the gritty obstacles, the apparent lawlessness, and the weirdos. The original KCDC and the yellow ledge. The scene along Bedford Avenue. In my second year at Queens College I moved to Greenpoint and lost touch with my friends in Nassau County. In Brooklyn, I only knew Colin from LI who went to Pratt University but we drifted apart. To make friends I rode my board.

On an otherwise uneventful summer's day, I randomly met Dan at the Monument by the foot of the Williamsburg Bridge. He knew some pros and skate industry people, worked at the Element Store in Times Square, and attended BMCC. He and his network, originally from Huntington, were deep into the innovator Bobby Puleo and the style that emerged from his cellar-door aesthetic, which might as well be called ‘Hipster Skateboarding.’ I was as big a part of it as anyone else, selected locations based on how ‘New York’ they looked, and started to merge fashion into my skater persona. Whereas Dan and his connections went for rolled up beanies, button down work shirts, sharp-crease highwater Dickies, and old school Vans, I went as tight as possible with everything, and shopped at American Apparel for v-necks, APC for raw denim jeans, and Trash & Vaudeville for a white Straight to Hell leather jacket.

In between commuting to school in my red Ford Focus on the LIE, I stalked the streets of the neighborhood to find bits and pieces of the terrain not yet tainted by a proliferation of tricks. As an extension of surf culture, one is charged with the responsibility of carving ownership from the city by either frequenting a locale often enough to form an occupation, or by dominating a popular or obscure obstacle with a trick so difficult or stylish the place becomes known by an individual’s name and what they did there. There is turf held down by this or that band of skaters, famous spots, and a sprawling street geography hit up by the unknown locals, and walked on by regular working people.

I wanted to be a pro skater when I was a teenager, but as the years passed I felt like the possibility of expression within skateboarding was culturally finite, and I did not want to trade my love in for a few years of product, followed by a lifetime of resentment and insecurity, which seems the conclusion to almost every pro’s career. They were good, someone noticed, they got free stuff, and a paycheck. Then they lost ambition, became irrelevant, and grew too old to compete, so abused alcohol and drugs, and entered the workforce at a late age with little to no experience, while carrying the burden of being a has-been. Like a boxer, an offensive lineman, a point guard, or a horse, who are all laid down to rest once their race is run, and then forgotten.

It was a mistake, however, to consider skateboarding as a separate entity. My relationship to it suffered until I regarded it as a part of my overall creative output. I can recollect several instances during my first year at Queens College when I felt torn between my past identity as a skateboarder and my burgeoning passion for writing. I neglected to encourage my skating for the first half of my 20s, placed the utmost importance on learning the intricacies of the English language, manically spent my time learning how to turn a phrase, absorbed as many stories as I could, stumbled through the library on campus, and searched for the ultimate truth. I replaced one obsession for another and only intermittently ran around in the street. In the process, my trick selection was boiled down to the basics. Like an artist, my early ‘career’ involved an attempt to master a host of pre-existing styles and led to a sort of pastiche repertoire. Over time, this gave way to a greater understanding of simplicity and I stuck with variations of ollies, kickflips, and shuvits, which resulted in what could be deemed a ‘classical’ style.

Altering my skills to suit this model allowed me to view it as an extension of all creativity. Something I did sometimes, rather than an overall identifying aspect of my personality. I don’t even really understand skateboarding in the strict sense anymore. It's a force of energy that occurs in and shifts the universe, and I just happen to be a participant.

In essence, skateboarding is disseminated through a colonial mindset. We explore ‘unknown territories,’ impose ourselves onto them, defile the property in the name of a holy extraction of expression, willfully antagonize or ignore whoever the rightful owner may be, and then vacate the premises once the mission is completed. Infiltrate-Destroy-Rebuild is the name of the CKY album on which “Flesh Into Gear” - the song Tom texted me - appears, but it is rare, if ever, that a skater accomplishes the lattermost item.

Capturing tricks on video or film, too, is equally as imperative to the accomplishment of the act, for this is undisputed proof that something went down, as well as the most effective means of emboldening existing tribespersons, gaining new recruits, spreading the gospel, and for brands, advertising.

Skateboarding relies on these methods of demonstration and visibility to serve its overall function in society and the marketplace. Unfortunately, because most skaters elevate their own perspective - in which the cement-world waits for manipulation or else lies dormant - above the common person's, it may be perceived as obnoxious and destructive. And typically, skaters look down at non-skaters because they have a skill that has historically defied societal prescription, and fall back on a bitter misinterpreted version of communism to justify their actions against property and peace.

The boroughs, and municipalities outside the city, have only recently executed a plan to contain and control this errant behavior. They built numerous skateparks. Easily accessible sanctioned arenas which cost millions of dollars. Facilities that monetize skateboarding and its practitioners, making them no longer players in a subculture engaging in rebelliousness on the fringes, but athletes on a closed course training for the future possibility of sponsorship and a professional trajectory, like any other sport.

This aspect of permission subdues radical thought or action and provides an opportunity to turn a street-kid into a poster child for the American Dream. The infinite amount of skateboarding content published online has also normalized it for the masses, along with increasing representation in movies, television shows, and commercials. But the inclusivity spawned by these changes is worthwhile, and the open attitude has broadened the playground to include a more diverse group, which I hope will endure. The boy's club bullshit - homophobia, transphobia, and misogyny - should have been dismantled long ago.

My own approach to skateboarding is intensely personal and I prefer to skate and not bother anyone. I tend to seek out obstacles on public or private-unoccupied property, such as one finds in industrial business zones. But the activity, like a human, is also unavoidably social, and sometimes I go to the skatepark or a DIY spot to put on a show for an audience, gain their respect after a strenuous battle, and connect with strangers without ever really speaking to them. A pure communication of the body, followed by an applause and hollering, which melts my heart and lightens my spirit like a cleanse.

VI.

On a sidewalk in Woodside is a short bank buttressed against a wall owned by the LIRR. I happened upon the spot while riding my beach cruiser around Queens, as I'm still on the lookout for previously untapped architecture, as far as I know, as mid-stage adulthood consumes me. I was immediately enamored with the remote location, the peeling gray paint, the pigeon shit, the graffiti, the elevated train track that hovers above, the worn multi-family house and shuttered business across the street, and the auto body shops and toxic warehouses down the way. The general uselessness of the concrete poured in such a particular way as to only suit a potential skateboard trick and nothing else. And when I traveled there, put the work in, and landed a stingy kickflip on the steep, almost impossible thing I felt joyful, free, and accomplished. Like the sandy-haired heroes of The Endless Summer, I continue to search out – in my estimation – the perfect wave, and sometimes in the crevices of nowhere, within NYC, I find it. And myself, too.

While I want to leave the rotten dirt undisturbed and simply focus on planting new metaphorical seeds into the machinery of the city, I recognize that the past has precisely guided me toward where I am and blame has no place in my heart.

So I sit here taking in the 60-degree evening breeze coming through the slightly open window in the corner of our bedroom. As the steel gate at the back entrance to Athens Square park, near the public restroom and the rogue cat colony, slams against the fence post and transmits the sound of two clashing medieval swords. I write myself into and out of existence, and contend with the blinking memories dumped in front of my eyes like the guts of a filleted fish on a stained, white cutting board at the fish market.