Cellar Doors: Pretty Words, Grimy Living, and Skateboarding (Published in Village Psychic March 19, 2024)

Words by Jeff Haber

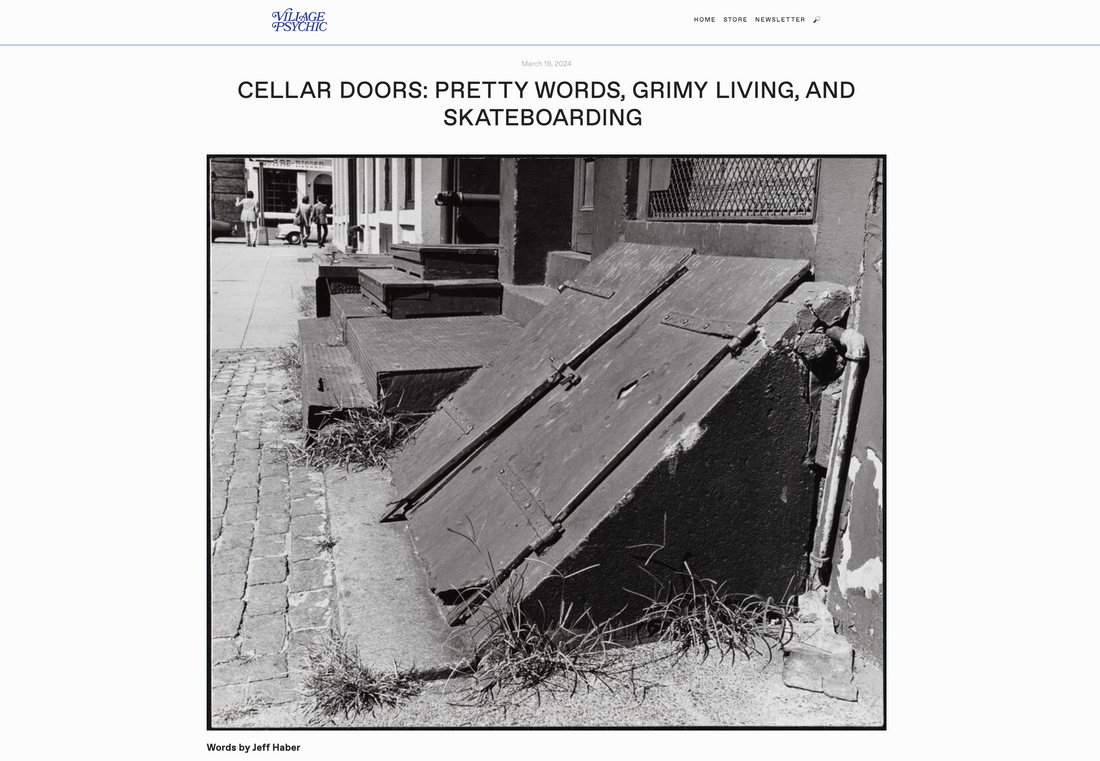

If you've spent any time walking in New York City then you've likely navigated over or around cellar doors. These steel doors, which are often diamond plated, lead into the basements and cellars of buildings. Most of these cellar doors lay flat on the ground – effectively creating a steel patch in what's otherwise a concrete walkway. They'll usually have two door components that fold open or closed, and a locking mechanism on the inside or outside. These cellar doors are primarily used by businesses, and you can often see them propped open, perhaps with a cone nearby while a worker brings goods up or down the hatch. Each one of these doors has its own personality, in terms of its design, construction, age, and texture.

As many skateboarders have observed, a select number of cellar doors are not flat. Instead, they are sloped or slanted, built at an angle and inclined. These slanted doors became popular skateboarding obstacles in the mid-2000s with the rise of gentrification, specifically in Lower Manhattan and North Brooklyn. The skateboarding community that was centralized in these sections of the city was then growing at a rapid rate with the influx of members of the creative class from the larger metropolitan area and well beyond. Suddenly, there was a proliferation of cellar door skateboarding.

Cellar doors appeal to skaters in more ways than one. Riding them allows practitioners to integrate a sense of flow into their performance on an otherwise relatively flat urban plain. They serve as a transition obstacle and evoke the spirit of vertical skateboarding in a landscape where that particular discipline is not readily accessible. Especially when the gentrification of Lower Manhattan and North Brooklyn was in its earlier phase, cellar doors represented a sort of artistic grittiness, which distinguished skaters in these locations as creative, rather than simply gnarly or technically proficient. Riding on a cellar door was a way to demonstrate one’s legitimacy as a New York City skateboarder.

When Did Cellar Doors Start Appearing in New York City?

In 1967, the late Dr. John Earl Rickert, then a professor at Kent State University in Ohio, published an article in the Annals of the Association of American Geographers, titled "House Facades of the Northeastern United States; A Tool of Geographic Analysis." In the piece, he writes of houses built between 1830 and 1850:

“The foundation of a house built in this era was without a cellar; however, a few houses had a half-cellar with an outside entrance and a crawl space under the remainder of the house. Even though the furnace was patented in 1815, it was not placed in the cellar until 1830 and did not become a ubiquitous fixture in the cellar until after World War I. The half-cellar of the period was used as a winter storage room for such foods as potatoes and apples.”

Rickert goes on to say that in the period of 1850 to 1865, "…the outside entrance to the cellar became a more common break in the stone foundation. During this era, the basement appeared." He describes the post Civil War era of 1865 to 1880 as "one of the greatest expansions in industrial, transportation, and financial activity," during which time, "brick was used along with stone for the foundation [of houses], and the full cellar appeared, although basements and half-cellars were still built. Along with the full cellar, the inside door to the cellar came into vogue as the furnace needed regular tending."

The development of cellars and basements underneath houses and buildings in the 19th Century in the Northeastern US, including New York City, accounts for the appearance of cellar doors as we know them. Access to storage areas and furnaces necessitated their implementation. What these underground spaces also did in New York was present a housing opportunity for newly arrived immigrants seeking cheap accommodations. This led to a notable rise in the population of what became known as "cellar dwellers." Today, living in a basement in New York City is legal under certain conditions, while living in a cellar isn't.

The New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development states:

“Basements and cellars are very different spaces and have different legal uses. A basement is a story of a building partly below curb level but with at least one-half of its height above the curb level. A cellar is an enclosed space having more than one-half of its height below curb level. Usually, if a cellar has any windows, the windows are too small for an adult to fit through.”

Starting around 1817, immigration into the US increased astronomically, bringing people from Ireland, Wales, Scotland, England, Germany, Poland, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Russia, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Many of those arriving came through the port of New York and a sizable portion of these folks stayed in the city. The Tenement House Problem, published in 1903 and edited by Robert W. DeForest and Lawrence Veiller, gives a brief history of that wave of immigration and its impact on housing. It reads, "…a 'cellar population' was in existence by 1822, as is shown by accounts of the 'Bancker Street fever.'" The work explains how different house types directly influenced the conditions of degradation among immigrant populations, especially those living in cellars.

An "old-fashioned frame house, once occupied, perhaps, by prosperous owners, had been turned over to tenement uses," while a "'tenement house,' [was] especially built for the purpose of containing several poor families, [and was] erected at the rear of the older building in the original yard." As a result of this arrangement, "filth, disease, and disorder" were rampant. For example, at 49 Elizabeth St sat a two-story frame house with an alleyway to a building in the rear. Pigs and stables were on the premises and "the yard had been completely boarded over, so that the earth could nowhere be seen" because "filth, liquid and otherwise, thus caused, the ground…[to be] impassable." Apparently, "these boards were partially decayed, and by a little pressure, even in dry weather, a thick greenish fluid could be forced up through their crevices." In any event, the work notes that "the use of the old, one-family dwelling as a tenement was mainly responsible for the growth of that great 'cellar population' which was the constant object of anxious attention on the part of philanthropists and sanitary reformers for many years." A description of 5 Jersey St. is given via an official city report from 1879:

“We then turned to go into the cellars, in which was a large and a small room (containing a cook-stove and sleeping-bunks). There was scarcely standing room for the heaps of bags and rags, and right opposite to them stood a large pile of bones, mostly having meat on them in various stages of decomposition…Notwithstanding the dense tobacco smoke, the smell could be likened only to that of an exhumed body.”

The Tenement House Problem further notes that flooding of cellars was a common issue. Starting in 1867, NYC law mandated that cellars had to be cemented, watertight, and damp-proof. And, "in 1887 a law was passed requiring that in every dwelling house arranged for two or more families above the first story there should be a separate entrance to the cellar from the outside of the building. This provision was enacted so as to enable firemen to have access to cellars to fight cellar fires." From 1867 on, the Board of Health had to issue a permit in order for cellars to be used as a dwelling and certain requirements had to be met, such as dimensions, drainage, windows, and access.

I could not personally find a source that explained the structural reasons for choosing a slanted door over a flat door, or vice versa. It seems reasonable, though, to assume that a cellar or basement more prone to flooding might benefit from a slanted door. Or, that the size of the vault over which the cellar door would be placed could dictate the style based on function or practicality.

In the 2001 history book Five Points: The 19th-Century New York City Neighborhood That Invented Tap Dance, Stole Elections, and Became the World's Most Notorious Slum, Tyler Anbinder speaks about immigration and cellar living:

“Most of the seediest boardinghouses were located in cellars, where rent was cheapest and there were few other uses for the space. Cellar dwelling peaked in the early 1850s, as desperately poor immigrants flooding into the city sought to save every possible penny in order to finance the emigration of spouses, children, parents, and siblings. A New York Tribune exposé at midcentury found that the Sixth Ward contained 285 basements with 1,156 occupants, meaning that approximately 1 in 17 residents lived in a basement. At least half that number probably lived in Five Points, many in cellar-level lodging houses.

…

Doctors who worked in the tenement districts could immediately spot the cellar dwellers among their patients. "If the whitened and cadaverous countenance should be an insufficient guide," explained one, "the odor of the person will remove all doubt; a musty smell, which a damp cellar only can impart, pervades every articles of dress, the woolens more particularly, as well as the hair and skin."

The First Instance of Play on a Cellar Door

Needless to say, tenement-era cellar doors in NYC are tied to the brutal living conditions that many immigrant groups had to endure because of overcrowding and limited economic opportunities. Yet, there's another less grim and more playful side to this subject. One that involves reimagining the cellar door long before skateboarding was even invented. What I mean is, children in New York City (and elsewhere) developed a form of play that relied on these doors – they slid down them. The population of children dramatically rose in 19th Century NYC, too. Many of them were part of the workforce, but they were still kids, and kids play. The Brooklyn and New York Society for Parks and Playgrounds weren't formed until 1889 and 1891, respectively. The New York City Department of Parks & Recreation states that in 1897 Mayor William L. Strong established the Small Parks Advisory Committee, with journalist Jacob A. Riis (author of How the Other Half Lives) as the committee's secretary. Playground facilities and play itself were considered integral to the moral development of children and even as a deterrent against engaging in criminality.

Skateparks in New York City are an extension of the same philosophy. The skateboard facility serves as a safe haven for the skater, which is crucial for the youth demographic, and gives children in particular the opportunity to join a positive community, rather than be forced to contend with the broader urban environment that views them as criminal or criminal adjacent.

Until playgrounds were more accessible to urban children, they played in the streets. Riis even took a photograph in 1890 of children sitting on a slanted cellar door with a title that reads, "A 'Slide' in Hamilton Street. (Shopkeepers hammered the cellar door full of nails to stop their using it as their grand slide)." You might interpret the nails in the door as a precursor to skatestoppers. Hamilton Street no longer exists, but used to be in Lower Manhattan between Catherine Street and Market Street, bordered north and south by Monroe Street and Cherry Street.

The popularity of sliding down cellar doors as a form of play was such that in 1894 the song "I Don't Want to Play in Your Yard", composed by H.W. Petri and written by Philip Wingate, refers to the activity. The chorus begins, "I don't want to play in your yard, / I don't like you anymore, / You'll be sorry when you see me, / Sliding down our cellar door." My favorite version of the song was recorded by Peggy Lee.

By the mid-20th Century, sliding down cellar doors became less common in terms of street play. A quote attributed to the newspaper correspondent William Chapman White, apparently published in the New York Herald Tribune in 1953 (though the original source material is unavailable), attributes this to a shift away from the slanted version. "The modern small home or apartment has…deprived today's child of…the pleasant summer afternoon activity of sliding down cellar doors. Just what happened to the slanted cellar door in this efficient age isn't clear; although cellars have remained, nothing has disappeared more quietly from modern life than these cellar doors." More than likely, as playgrounds popped up and became widely available, and architectural shifts in NYC occurred, children became less interested in hunting down a slanted cellar door because they had better, easier play options.